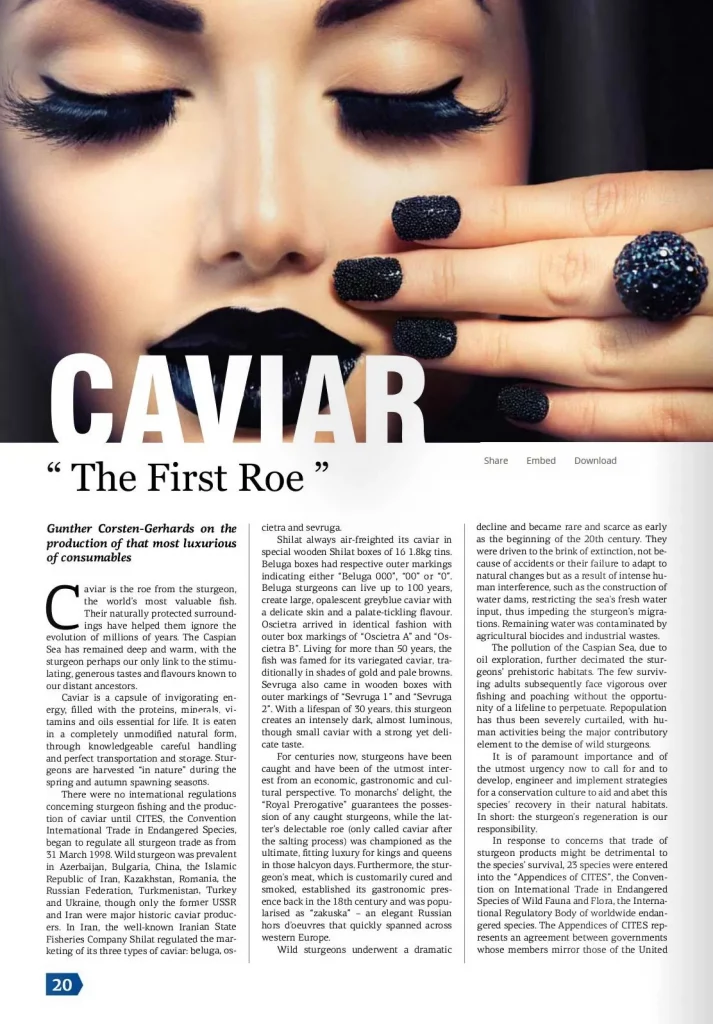

Caviar is the roe from the sturgeon, the world’s most valuable fish. Their naturally protected surroundings have helped them ignore the evolution of millions of years. The Caspian Sea has remained deep and warm, with the sturgeon perhaps our only link to the stimulating, generous tastes and flavours known to our distant ancestors.

Caviar is a capsule of invigorating energy, filled with the proteins, minerals, vitamins and oils essential for life. It is eaten in a completely unmodified natural form, through knowledgeable careful handling and perfect transportation and storage. Sturgeons are harvested “in nature” during the spring and autumn spawning seasons.

There were no international regulations concerning sturgeon fishing and the production of caviar until CITES, the Convention International Trade in Endangered Species, began to regulate all sturgeon trade as from 31 March 1998. Wild sturgeon was prevalent in Azerbaijan, Bulgaria, China, the Islamic Republic of Iran, Kazakhstan, Romania, the Russian Federation, Turkmenistan, Turkey and Ukraine, though only the former USSR and Iran were major historic caviar producers. In Iran, the well-known Iranian State Fisheries Company Shilat regulated the marketing of its three types of caviar: beluga, oscietra and sevruga.

Gunther Corsten-Gerhards on the production of that most luxurious of consumables: CAVIAR

Shilat always air-freighted its caviar in special wooden Shilat boxes of 16 1.8kg tins. Beluga boxes had respective outer markings indicating either “Beluga 000”, “00” or “0”. Beluga sturgeons can live up to 100 years, create large, opalescent greyblue caviar with a delicate skin and a palate-tickling flavour. Oscietra arrived in identical fashion with outer box markings of “Oscietra A” and “Oscietra B”. Living for more than 50 years, the fish was famed for its variegated caviar, traditionally in shades of gold and pale browns. Sevruga also came in wooden boxes with outer markings of “Sevruga 1” and “Sevruga 2”. With a lifespan of 30 years, this sturgeon creates an intensely dark, almost luminous, though small caviar with a strong yet delicate taste.

For centuries now, sturgeons have been caught and have been of the utmost interest from an economic, gastronomic and cultural perspective. To monarchs’ delight, the “Royal Prerogative” guarantees the possession of any caught sturgeons, while the latter’s delectable roe (only called caviar after the salting process) was championed as the ultimate, fitting luxury for kings and queens in those halcyon days. Furthermore, the sturgeon’s meat, which is customarily cured and smoked, established its gastronomic presence back in the 18th century and was popularised as “zakuska” – an elegant Russian hors d’oeuvres that quickly spanned across western Europe.

It is of paramount importance and of the utmost urgency now to call for and to develop, engineer and implement strategies for a conservation culture to aid and abet this species’ recovery in their natural habitats.

Gunther Corsten-Gerhards Tweet

The Sturgeon’s CITES listing aims to reduce and eventually completely eliminate the illegal trade of caviar on the world market. All Acipenseriformes species are controlled by various regulatory and enforcement means, such as Quota Control, Permits, Traceability and Coded Labelling. It is hoped that these implementation and enforcement structures will strongly contribute towards the conservation of sturgeon stocks, but in particular will aid the survival of remaining wild sturgeon stocks in the Caspian Sea. It is the world’s largest landlocked sea and home to six sturgeon species, which collectively used to provide in excess of 90 per cent of the world’s annual caviar yields.

It all began with the beluga sturgeon as catalyst, being isolated as the Caspian Sea’s most affected and endangered species. This triggered during the following years a number of temporary import and export bans by both the US Fish and Wildlife Services and also CITES.

In short: The sturgeon’s regeneration is our responsibility.

Wild sturgeons underwent a dramatic decline and became rare and scarce as early as the beginning of the 20th century. They were driven to the brink of extinction, not because of accidents or their failure to adapt to natural changes but as a result of intense human interference, such as the construction of water dams, restricting the sea’s fresh water input, thus impeding the sturgeon’s migrations. remaining water was contaminated by agricultural biocides and industrial wastes.

The pollution of the Caspian Sea, due to oil exploration, further decimated the sturgeons’ prehistoric habitats. The few surviving adults subsequently face vigorous overfishing and poaching without the opportunity of a lifeline to perpetuate. Repopulation has thus been severely curtailed, with human activities being the major contributory element to the demise of wild sturgeons.

It is of paramount importance and of the utmost urgency now to call for and to develop, engineer and implement strategies for a conservation culture to aid and abet this species’ recovery in their natural habitats.

In short: the sturgeon’s regeneration is our responsibility.

In response to concerns that trade of sturgeon products might be detrimental to the species’ survival, 23 species were entered into the “Appendices of CITES”, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, the International Regulatory Body of worldwide endangered species. The Appendices of CITES represents an agreement between governments whose members mirror those of the United Nations ( UN ) .